She remembers life before communists took over

Rhee Soon-ja has vivid memories of her father reading the Bible to her and her six siblings when they were children in northern Korea. She remembers that the verses were printed vertically, rather than horizontally. And although now 82 years old, she can still picture the phrase “Christ Is Lord of This House” hanging from a wall in their home.

“My parents prayed that God would use me as His servant,” she said, recalling another childhood memory. “I grew up dreaming of becoming an evangelist.”

Those were the days before Korea split into North and South, communist and free. Those were the days when the Christian faith flourished in northern Korea.

“There were many Christians,” Soon-ja shared from her living room in South Korea. “I attended the Methodist Church. All the congregations gathered every Sunday.”

When Soon-ja was a young girl, her family was among the first to experience persecution under the rule of Kim Il Sung, North Korea’s first leader. Today Christianity is illegal there, and those who choose to follow Jesus are sent to a concentration camp, where they are starved, tortured and often killed. Soon-ja has experienced a lifetime of pain, but when she looks back on her life she sees God’s hand in it all.

Soon-ja was born in 1937, the fifth of seven children. Her father, a mine worker, was known for his Christian faith — well enough that many people, including his relatives, criticized him for it. They thought he was too bold in sharing the gospel. But having read the Scriptures, he knew persecution was simply part of following Jesus.

“He taught us that the more we are persecuted, the more we need to trust in the Lord,” Soon-ja recalled.

At the end of World War II, when Korea was freed from Japanese colonialism and divided into two countries, the brutal Communist Party in the north forced most pastors to flee to the south. Kim Il Sung became North Korea’s first premier in 1948, the year North Korea and South Korea gained formal independence as sovereign nations.

“As the Communists became more powerful, even my father became uneasy,” Soon-ja said. “He asked three of my brothers to move to South Korea to earn a living. But my father did not leave North Korea. When our pastor left, our father took his place and kept the church.”

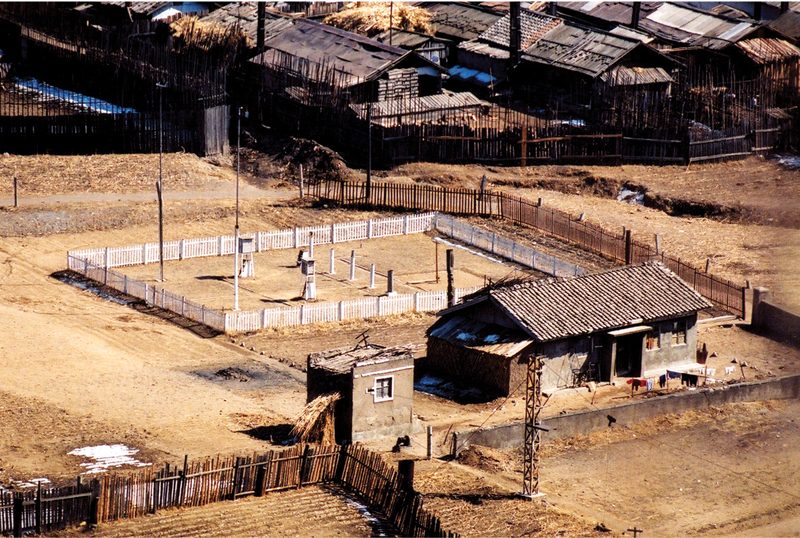

The Communists began to occupy church buildings as North Korea gradually became an atheistic state. “Many of the church buildings were destroyed, and we had to begin worshiping in our own houses,” Soon-ja said.

Around that time, Soon-ja had to complete an entrance exam and interview to enroll in junior high school. But when administrators saw that she had stated her religion as “Christian,” they denied her application, and her father had to find another school for her to attend.

These subtle forms of persecution quickly became the norm, and life became increasingly difficult for Soon-ja’s family. The government was already promoting the idea that religion is a drug used to control people and was mandating that all North Koreans follow the official state religion, Juche, venerating Kim Il Sung.

“My father used to say, ‘No matter how much persecution there may be, we must persevere; we have to endure persecution even when we don’t have anything to eat,’” she recalled.

Soon-ja’s family took time to worship God in their house regardless of the obstacles presented by the atheistic Communist government. They were aware, however, that they could be killed if they were ever caught.

LOSING HOPE

In the mid-1960s, Soon-ja’s brother hosted a prayer gathering at his house. Recognizing that many people were worshiping

Kim Il Sung as a false idol, he burned a portrait of the North Korean leader following their time of prayer.

One person at the prayer meeting reported the act to authorities, and Soon-ja’s brother was quickly arrested and sentenced to 20 years in prison. In addition, Soon-ja’s family was separated and forced to leave Pyongyang, and her parents were required to work in mines for several months.

Soon-ja’s brother thought hanging a portrait of Kim Il Sung in his home (as all North Koreans are required to do) was idolatrous, so he burned it.

Soon-ja was 28 at the time and had been married for three years. She and her husband, whose relatives were high-ranking Communist officials, had two young sons. Since Christians were considered enemies of the state, the government ordered her husband to divorce her, giving him sole custody of their 3-year-old and 8-month-old sons.

“My husband asked me to go out from the house,” she said tearfully. “Our 3-year-old boy was holding my leg and asked me not to go anywhere. At that moment my husband kicked me out, and he started beating the boys. They kept asking, ‘When are you coming back?’ To comfort them, I told them, ‘I will come back after a few days.’ That was the last time I saw them.”

After losing her husband, children and home because of her Christian faith, Soon-ja lost all hope and began to waver in her faith. “I remember standing on the riverside thinking of committing suicide,” she said, “but the words of my father kept me from doing it. He had said that our lives are not our own but God’s. I couldn’t die.”

After her parents were released from their work in the mines, Soon-ja moved in with them. Her mother was then able to visit her brother in prison, but what she saw was disheartening. On the first visit, it was clear to her that he was malnourished and had been severely beaten. On the second visit, guards told her that he wasn’t available. And later, the family learned that he had died.

“We think my brother was killed as an example for other Christians because the government hates religion,” Soon-ja said. “The moment I learned that my brother died in prison, I felt there was no God. I lost my hope and vision as an evangelist.”

A NEW FAMILY

In the early 1970s, Soon-ja’s father told her about a North Korean widower who might make a good husband for her. The man, who also had Chinese citizenship, had eight children, and Soon-ja’s father thought Soon-ja would be a good mother for them. He worried that without a husband she would have no future. Soon-ja’s mother opposed the idea because the man was not a Christian, but that was not an obstacle for Soon-ja, whose faith had long faded. Although she initially refused to consider it, she eventually decided to marry the man.

“It wasn’t easy to raise another woman’s children when you have had to leave behind your own children,” Soon-ja said. “However, my heart grew toward the children.”

Eventually, Soon-ja and her second husband had two more children, giving Soon-ja 10 children to raise. While her husband and children all had Chinese citizenship, Soon-ja was never able to obtain it despite her husband’s hard work to get them out of North Korea.

In late 1994, she obtained a three-month visa allowing her to join her family on a trip to visit her husband’s relatives in China. While walking around in a Chinese city with her family one day, she heard someone reciting John 3:16, a verse she remembered reading in her youth. When she turned around to see who it was, no one was there. She asked her husband if he had heard anything, but he had not.

“I stopped praying after I lost my brother,” she said. “I stopped worshiping. I never thought about God, but in that moment I was stunned by the words in my head. In that moment, I said, ‘I have to go to church.’”

Soon-ja soon began an intense Bible study with a pastor she met in China, but her husband never joined them. As they studied God’s Word, the pastor encouraged Soon-ja to flee North Korea with her family and live in China. They even set a date for her to flee.

As Soon-ja’s visa expired, she left her family in China and returned to North Korea. But as the date approached for her to flee, she could not muster the courage to make the dangerous journey on her own. She did, however, remain in contact with the pastor who had encouraged her to leave North Korea.

Two years later, at age 60, Soon-ja decided she was ready to escape. On a hot summer evening in July 1997, she told some neighbors that she was going to bathe in the Yalu River, which serves as part of the border separating North Korea from China.

“I didn’t feel afraid,” she said. “I already had lots of experience in suffering. It was nothing to me.”

A CALLING REALIZED

As she waded into the Yalu River, Soon-ja sensed that the secret police were watching her. Her heart raced as she quietly trudged through the cold water, which gradually rose to the level of her chest.

After climbing out of the river on the Chinese side, apparently unnoticed by North Korean border guards, she met the pastor and reunited with her family. At the pastor’s suggestion, the family soon moved to a small Chinese town, where they lived for three years. During that time, Soon-ja continued to grow in faith; her husband, who never became a follower of Jesus, was finally able to buy her Chinese citizenship for $1,000.

Soon-ja’s two youngest children, then in their late 20s, decided to move to South Korea, and in 2001 she and her husband moved there to be near them. Her husband, however, was allowed to stay for only three years before returning to China, where he died in 2011 from an illness.

“I had to start working as a housemaid immediately to survive,” Soon-ja said. “Fortunately, I met a good homeowner who was a deacon at a church.”

Today, Soon-ja continues to live in South Korea with her son and granddaughter. She has graduated from a VOM-sponsored discipleship program and participated in missions trips, including one to China. During the trips, she meets with other North Korean women and tells them how she recommitted her life to Jesus.

“I cried a lot when I met North Korean women in China who were sex-trafficked,” she said. “I shared my testimony. They were in their 30s and 40s. For them I was like a mother. I just hugged them, and they were just holding my hand and starting to cry. I really felt pain when I saw them.”

Soon-ja is not sure she would try to visit her two oldest sons if the border with North Korea opened during her lifetime; she thinks it would be too painful. She continues to pray for their souls, but she knows they are living a comfortable life in North Korea because of her first husband’s social class. “I have a heart of mother’s love toward them, but I don’t worry about them,” she said, crying.

Looking back on her life, she said her biggest regret is that she didn’t listen to her father’s wishes when she was younger.

“If I can meet my parents [in heaven], I want to say sorry to my father because I couldn’t live as a good Christian when I was in North Korea,” she said. “My father kept asking me to be an evangelist, but I didn’t follow this.”

Her regrets are slowly fading, though, in the light of an ever-growing faith that her father once prayed she would have. “God is using me and my vision, and now I am living as an evangelist,” she said. “I think maybe my parents’ prayer is being answered.” – Voice of the Martyrs

To learn more about the ministry of Voice of the Martyrs, go here