As is my custom when walking through art museums, I look for elements of Christian influence. My recent visit to the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art was no different.

At the museum are two exhibits: Brad Kahlhamer’s Swap Meet (which I loved, particularly his ink-infused watercolors and notebooks) and Beverly McIver’s stunning portraits in an exhibit entitled Full Circle.

I could go on about both. Looking for Kahlhamer’s “third space” ideology as an adopted Native American growing up in a German Lutheran family is fascinating exploration of American identity. And his spiritually infused sculptures (dream-catcher-like with bells and jingles), would make for a mindful exploration of the integration of amalgamated worldviews. Kahlhamer gave me something to muse.

But it was McIver’s “Dear God” series of portraits that I note here.

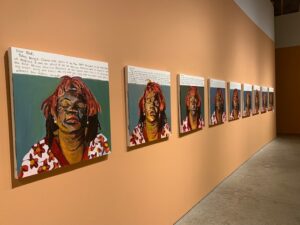

In nine similarly rendered paintings, McIver’s portraits with prayers are a unique look at the daily spiritual life an artist.

In the oil-on-canvas paintings one sees a woman, eyes closed with flowered shirt, painted upon a gray blue back. The repetition is reminiscent of daily existence, the routine of regularity. In the case of McIver’s portraits, the regularity is of a woman in prayer.

Some of the prayers are political, noting how proud she is that Barack Obama was elected president, the first bi-racial President of African descent.

Other prayers are personal. Ranging from helping someone find an apartment, to dealing with health issues, to walking with someone to an abortion clinic.

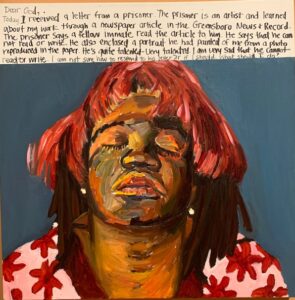

Then there are the poignant prayers, noting unemployment, homelessness, and prisoner-relations. Here’s the Prisoner Prayer (my name, not McIver’s):

“Dear God,

“Today I received a letter from a prisoner. The prisoner is an artist and learned about my work through a newspaper article in the Greensboro News and Record. The prisoner says a fellow inmate read the article to him. He says that he can not read or write. He also enclosed a portrait he had painted of me from a photo reproduced in the paper. He’s quite talented—very talented. I am very sad that he cannot read or write. I am not sure how to respond to his letter or if I should. What should I do?”

What I love about McIver’s prayer is that it is comforting (“He’s quite talented”), compassionate (“sad he cannot read or write”), and concerned, asking God, “what should I do?”

In McIver’s artwork and prayer, we get a glimpse of an artist translating her art as prayer, a type of modern iconography.

As I wrote in my book Tilt: Finding Christ in Culture concerning iconography, “For some Protestants, discussing icons can be like someone slurping a soda during a movie: it can grate on the nerves. But not for me. As one who is influenced not just by [Pavel] Florensky but also avant-garde icon painting, I can appreciate what the ancient Christian artists were aiming at: seeking transcendence through the use of art.

“The practice of icon painting was established in the second to fourth centuries AD. Icons are a painterly means to represent biblical truth, causing us to look beyond the image to the Image of God in Christ. As an early church council inferred, that whatever a doctrine says with words, the icon carries with lines and colors.[1] Icons are not meant to be perfectly realistic portrayals of biblical events but physical representations that reveal metaphysical truth, a type of spiritual perspective that looks beyond this world. As Andrew Spira put it, ‘The definitive characteristic of icons goes beyond artistic or sociological significance; it lies with their metaphysical identity.’[2] Icons are emblems of God’s eternal ideals, His thoughts made visible. They typify transcendent reality: a means to ponder God’s works as they take on physicality through His creation…”

What I find in McIver’s modern iconography is that she delves into the transcendent world, positioning portraits as prayer. Her paintings take on physicality to ponder her daily cares and concerns, an artist within the world she resides; an artist humble enough to ask God for guidance and to share her prayers with a viewing audience. In her “Dear God” series, McIver demonstrates her “metaphysical identity” with those of us who can join her prayer group, grasping for God to receive and respond.

[1] See Seventh Ecumenical Counsel.

[2] Spira, The Avant-Garde Icon, 8.