After a blistering 11-day campaign from their strongholds in the north to Damascus, Syria’s capital in the south, rebel forces succeeded this weekend in toppling the 24-year reign of dictator Bashar al-Assad.

capital in the south, rebel forces succeeded this weekend in toppling the 24-year reign of dictator Bashar al-Assad.

The main rebel power behind the blitz is Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a local militant group that appears to be motivated both by Islamism — the group was founded as an affiliate of al-Qaida and, despite severing ties with the group, continues to espouse al-Qaida’s Salafi-jihadist ideology — and nationalism.

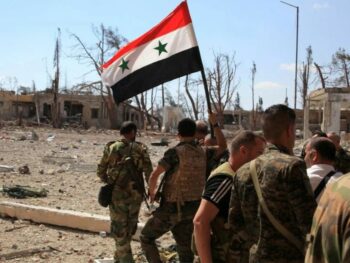

As they descended southward toward Damascus, capturing cities along the way, HTS fighters were joined by other groups similarly disaffected by the Assad regime and eager to join a movement gaining momentum in the effort to topple the unpopular dictator.

Assad was the latest in a family dynasty that had ruled Syria since 1971. During that time, the Syrian people were brutally restricted and suffered through the systematic stripping of their basic rights and freedoms — including the right to worship freely. Christians and other disfavored religious groups long suffered severe persecution under the Assad regime.

While many in the country are celebrating the downfall of a dictator who repeatedly ordered the use of chemical weapons against his own people and murdered thousands of opponents, religious minorities and international observers alike are waiting to see what an HTS-led government will look like and whether HTS will work to create a rights-based order.

HTS Goals and Ambitions

HTS has been designated as a foreign terrorist organization by the United States since 2018 after it split from al-Qaida. HTS’s predecessor organization, Jabhat al-Nusra, was similarly designated and was founded in 2011 by Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, who today is the leader of HTS.

Even in this earlier form, al-Jolani and his group were always focused on opposing the Assad regime — a significant fact as it created an early emphasis on nationalism rather than simply jihadism.

In the years since, the group has continued to heavily emphasize its political aspirations in Syria, at times over broader themes of jihadism. Though statements by al-Jolani do sometimes hint at the broader aims of a global Islamic caliphate, HTS has, in recent years, instead focused its rhetoric on establishing rule over Syria and expelling pro-Assad Iranian influence from the country.

Al-Jolani’s early years as a militant were spent fighting for ISIS in Iraq. After eight years as an ISIS fighter, when he returned to Syria in 2011, it was as a representative of Islamic State founder Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his vision of global jihad and a worldwide Islamic caliphate. Still, HTS represents a break from that ideology in favor of Syrian nationalism, and the group has fought against al-Qaida and ISIS influence in Syria in recent years.

In recent days, as his forces have seized city after city, al-Jolani has worked to project an image of relative tolerance and acceptance for Christians and other religious minorities, including Shiite Muslims.

“Diversity is our strength, not a weakness,” al-Jolani declared in an edict upon capturing Aleppo en route to Damascus. His appeal appeared to be for a united Syria and a broad-based future for the country.

Observers were surprised at the orders to protect religious minorities. Still, initial skepticism was met with peace in the Christian neighborhoods of Aleppo, and fighters are reported to have gone house-to-house repeating assurances of tolerance.

In videos circulating online, a Christmas tree is visible in a marketplace located in a predominantly Christian area of the city after the rebel takeover, and fighters are reported to have permitted Christmas celebrations to continue.

In areas held by HTS in recent years, it reportedly allowed some degree of freedom. The group, for example, has permitted smoking and other practices that are prohibited under a more fundamentalist interpretation of Islam. Other sources, though, report that HTS consistently harassed and detained all who were critical of the group or strayed from their religious doctrine, lax as that might be.

The initially positive signs in Aleppo do not, however, suggest that Syria is entering a new period of interfaith tolerance or widespread religious freedom. Reports from the capture of Damascus include incidents of rebels inquiring into the religious identity of residents, suggesting that religion may continue to act as a point of tension.

While al-Jolani’s immediate focus is to set up a functioning government and is thus motivated to bring as many communities as possible into cooperation, he is still an avowed proponent of the Salafi-jihadist ideology. He has much deeper roots as a persecutor of religion than a promoter of its free practice.

As the international community watches to see what type of government will replace the Assad regime, hundreds of thousands of religious minorities in Syria are watching, too. For them, the new government’s respect for religious freedom is an intensely personal unknown.

Should al-Jolani continue to signal support for the rights of Christians and others, that would be a fundamental shift for the better. But that outcome is far from guaranteed, and a reversion to his old ways under ISIS and al-Qaida would be disastrous for these already vulnerable communities that suffered so much under Assad. — International Christian Concern