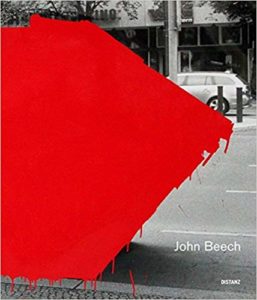

A Discussion with British-American artist, John Beech

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO—I sort of felt like famed journalist Gay Talese as he watched Frank Sinatra in a bar. In his much-admired article “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” [1], Talese never got close enough to the celebrated crooner to interview him, so just watched—as a fly on the wall, as Sinatra almost got into a fight in Beverly Hills.

The artist John Beech (b. 1964) is not Frank Sinatra; nor were we in a bar. And I did end up speaking with Mr. Beech. And instead of Beverly Hills, we were at Charlotte Jackson Fine Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico. But the fly-on-the-wall bit, I did do. I arrived early before the opening of Beech’s exhibit, Outside the Drift, to get a glimpse of his art. I didn’t expect to see the artist.

But there he was—glasses, dark pants, button-up shirt, and black shoes talking to a man using a cane. I casually strolled by the two hearing words such as “Germany” and “art,” all spoken by the elderly gentleman. There was no context to the conversation, just a whisper of words. The whole time I watched Beech from across the gallery floor. Charlotte Jackson later joined them, taking work off the wall with white gloves.

As I watched, a few things struck me about John Beech.

First, he was engaged with the conversation, showing the elderly man due respect and responding when appropriate. Second, he smiled often, nodding, and providing feedback when necessary. Finally, his attention was clearly on the man, not on me or the owner of the gallery, Charlotte Jackson, who had come over to me to say hello and let me know a little about the exhibit.

I was impressed with what I was seeing. John appeared to be a kind man. Not that I was shocked by this, but it did provide balance to my initial thoughts of him I held as a teenager in California.

A little history is in store.

As a member of a post-punk band in the 1980’s [2], our small crew of band members loved two things: music and art. We were always looking for something new, particularly in the California Bay Area. This is where Beech came in. As I became familiar with artists working in California, I stumbled upon Beech’s work. My initial thought was that his work was punk rock, irreverent, cynical, and derisive, a modern take on Dada. Around 1989—when we were recording our first and only record—Beech was showing his work in San Francisco. Even the San Francisco Chronicle picked up on his looming success, publishing an article entitled, “Promising Debut of John Beech” (written by Kenneth Baker in July 1989). To say the least, I was interested. I followed his work from a distance.

Little did I know that Beech wasn’t some disrespectful, street-wise punk rocker, but an educated man originally from Winchester, England. And as a graduate of the University of California, Berkeley with a B.A in studio art, Beech was a trained artist. But I didn’t learn this until much later. For the time, his work—which ranged from car mats, painted dumpsters, and scrapyard sculptures—resonated with me, a teenager interested in art and culture.

John Beech’s career blossomed. He exhibited around the globe, won awards (such as the Pollock-Krasner Foundation) and continued to stretch the notion of what minimalist, abstract, and contemporary art could become. With countless articles, books, and attention given to his art, Beech’s work was getting the care it deserved. It seemed to culminate with a retrospective exhibit in 2004, entitled “John Beech Works: 1989-2004.” And then an exhibit at a church in Solothurn, Switzerland, where Beech’s de-constructivist art was a fascinating contrast to the stained-glass windows [3].

Since then, there’s no looking back. Beech continues to produce—now from his studio in Brooklyn, New York—engaging art, cultivating work that, as his artist statement conveys: adheres to the actual, destroys an illusion, highlights “the presence of an object,” shows “the familiar rediscovered,” signals “the overlooked examined,” and has the “stasis that contains all motion.”

You can understand why I was reluctant to interrupt his conversation between Beech and the gentleman with the cane—it may have been deep.

But after the gentleman left, Charlotte introduced Beech to my wife and me. Upon meeting him, my respect grew. As I observed, Beech was kind and considerate, giving as much attention to us as to his work.

Beech began by telling us what brought him to the United States. “I grew up in England. But my dad was in the tech industry,” he started. “So we moved to the Bay Area in 1981 where he worked with HP before moving to Oracle for the latter part of his career. I’ve since relocated to the East Coast, but my parents still remain in California, now in Monterey.”

How was your time at Berkeley? “It was great. I was able to study with fine instructors such as David Simpson and Robert Hartman and begin to develop a sense of what it means to be an artist and acquire a voice to my work. I traveled around Europe with a girlfriend the summer of 1985, England, France, Spain, Italy. Also took the boat to Morocco and eventually to the ancient city of Fez. It was there that I realized there was no turning back for me, that I was an artist, that my response to this amazing place was as an artist. Even though there are incredible buildings there, I related to them not as an architect, but saw them as active sculpture. And painted surfaces. I also saw the value of recycling materials, the idea of reuse and potential in ordinary materials.”

Beech, then, turned the questioning on me, asking about my band. When I told Beech my band was an underground group with little airplay—except on college radio, he asked if I knew of a band one of his friends fronted. Sadly, I didn’t. But the connection to the Bay Area was there.

I asked about his move to Brooklyn. “It was a wise move. I’ve been there for twenty two years now. I purchased a building over ten years ago. And with a new baby boy, there is another dimension, new ways to understand time, keeping focused in the present as ever.”

Is your new space dual purpose, I ask? “Yes. On one side is my studio, and the other side of the building is our family’s living space. But in addition to the home, Brooklyn has turned into a nice travel portal, an in-between place, for me. With frequent visits to Europe and California, I’m regularly on the move.”

I asked him about his current exhibit at Charlotte Jackson Fine Art. “To tell you the truth I was a little nervous. I didn’t know what I would be able to come up with for the on-site works. It turned out that I was lucky to come across some 4 by 8 foot sheet material that I hadn’t encountered before. In the end the works seemed to make themselves.”

The new works Beech is mentioning are large industrial board sculptures, fastened to the wall with metal mending plates. The stamped company name of the sheet material remains visible, though now employed as a compositional element on the surface of this makeshift ‘painting’. A flat sculpture that presents itself as a painting, affixed directly to the wall.

I point to four black and white paintings Beech recently completed. “These are my favorite,” I say, “brilliant.” The paintings are aptly named Paintings #172, #173, #181, and #182 respectively. Charlotte agrees. “I love to see the artists’ hand at work; and with these, John’s hand is quite prominent. They’re lovely,” she says conclusively.

John smiles, and though provides no interpretation, shows gratitude—through gestures—for our appreciation of his work.

As a fan of the sport, I couldn’t leave without asking Beech about football (soccer here in America). I mean, don’t all Brit’s love the Beautiful Game? “I’m not huge fan, I’m more of a tennis guy” he begins—dashing my plans for football talk, “but my father is. He’s a Leicester City man. When Leicester won the Premier League in 2016, it was a big moment for him. Dad makes it a point to attend a couple of games when he gets a chance, flying from California to England. But now he’s 84, not so often. He enjoys wearing his Foxes cap back in Monterey.”

We converse for a while longer, an almost do-you-remember-this type of thing, reminiscing about the Bay Area. Eventually, Beech asked if I’d like a book. How could I turn one down? He walked into the back and signed it.

Likewise, Charlotte was kind enough to provide me with an artist’s information pack. As I thumbed through it later, I came upon a Spotlight Charlotte’s team had drawn up on John Beech. The summary of Beech’s art reads:

“Where John Beech’s work is concerned, expect the unexpected. Rather than resorting to the traditional materials of a painter or sculptor, Beech often uses objects that are so ordinary and utilitarian that most of us look right past them. Presented in his sometimes quirky, always intriguing way, they become part painting, part sculpture, and are entirely recognizable as finely wrought works of art. Consider the concrete ‘bumpers’ that keep your car from moving too far forward in a parking lot. Most of us would never give them a second thought; John Beech sees them (and potentially everything else) as artistic forms and fabricates replicas of them, altered just enough to provide the viewer with a strong jolt of the unpredictable.”

Unpredictable is a fine word to use in relation to much of Beech’s art.

And concerning the current exhibit at Charlotte Jackson Fine Art, writer, Dr. Michaela Kahn, provides valuable thoughts in relationship to Beech’s artwork: “Strange shapes. Thick whorls of paint. Photos of everyday objects like dumpsters or movers’ dollies set within a canvas and covered over by layers of paint… [Beech’s art] resembles nothing so much as a walk through a museum of artifacts from some unknown and yet hauntingly familiar culture.”

The description continues: “This sense of chance and intuitive exploration pervades all of Beech’s work. For example, Beech explains that with his small paintings he handles and turns them as he works – adding layers and dimensions, looking for a ‘development or orientation that might take the painting to being finished.’ the history of that process is apparent on the pieces themselves – where fingerprints and marks are visible on the edges.”

Artifacts. Hauntingly familiar. Chance. Intuitive exploration. Beech’s language uses both common and uncommon artistic vocabulary.

Kahn summarizes Beech’s practice as thus: “John Beech is an artist not confined to one method or mode. Paintings, photography, sculpture. plaster, wood, Plexiglas, paint, metal, canvas, glue, hardware, and often the ‘found objects’ of his own studio: paint stir sticks, plywood, acrylic sheet scraps, rags. While there is a distillation of 20th century ideas in art here – particularly Minimalism, with a dash of Dadaism – the persistent element in Beech’s aesthetic seems to be a centering and foregrounding of art-making itself. “

As I read Kahn’s insight—and later the book about Beech—I began to appreciate Beech’s work and life much more, learning about an astute and engaging artist.

Upon our leaving the gallery, Beech turned to my wife and I and said, “Thanks for the enthusiasm about my art. It means a lot.” I thanked him for the book. But thinking to myself, how could I not be enthusiastic! As the press release by Kahn states, “Beech demystifies the elevated status of art-making by showing us its everyday roots…” And in my short time with Beech, he demystified my teenage image of him as an irreverent punk artist, and instead demonstrated an artist of conviction and care, a man firmly rooted in family and his work; or, as the press release states, “one step closer to the ground, to the material insistence of reality.”

And maybe that’s what Beech’s art does: connects us to the core of what we share in common as human beings; that simple and seemingly insignificant things matter; that making art is the art, just as living life is life.

And unlike Sinatra, Beech didn’t have a cold, nor did he incite a fight—as an in-your-face punk artist (he’s partial to reggae, by-the- way). Instead, he inspired us with his art and life, reaching for a common humanity intermixed with an uncommon narrative, moving us towards a rare vision of art and beauty.

For more information about John Beech, visit his website: www.johnbeech.com