An overview of Native American contribution to popular music and the American church.

ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO (ANS)—At a recent Albuquerque screening of PBS’s documentary, Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World, I was reminded of the Native American contribution to American music, specifically rock and roll. As winner at many film festivals, including Sundance, Rumble follows the impact Native musicians had on American popular music, from Charlie Patton (blues) and Link Wray (rock and roll) to Robbie Robertson (rock and folk rock) and Randy Castillo (heavy metal). Rumble is enlightening, informative, and inspiring.

Yet it made me think: much like Native American contribution to popular music has been overlooked, so, too, the contribution to the church. Even in the midst of horrible treatment, massive misunderstanding, and cultural genocide, many Native Americans had a major impact on the life of Christianity within the United States.

To help provide a basic understanding on the influence of Native Americans on the American church, consider these five important figures. Though there are many more, I choose two from early American history, and three from recent American history as an overview based upon writings we can read and study.

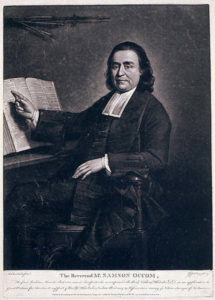

Samson Occom (1723-1792)

Occom was a member of the Mohegan nation, a tribe whose homeland is in the Connecticut region. As a Presbyterian minister, Occom published several works ranging from hymns studies and theology to herbal medicines. Occum was the first Native American to publish writings in the English language. In 2006, Oxford University Press published his complete works, a welcome addition to American studies.

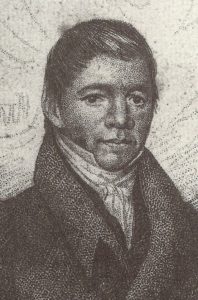

William Apess (1798-1839)

As a member of the Pequot Nation, Apess was born in Massachusetts, where he studied to become a Methodist pastor. As a Christian author, clergyman, and activist, he’s considered “perhaps the most successful activist on behalf of Native American rights in the antebellum United States.” The University of Massachusetts Press released his collected works in 1992.

Clara Sue Kidwell (b. 1941)

Chippewa and Choctaw scholar and author, Kidwell has written extensively on the topic of Native American theology and influence. Kidwell began the American Indian Center at the University of North Carolina, where she is a professor. Her book A Native American Theology is a helpful look at the diverse beliefs within Native American culture.

Dayton Edmonds (b. 1944)

Edmonds is a Methodist minister, storyteller, author, and artist. As member of the Caddo tribe, Edmonds expresses his role as a clergyman-storyteller as thus: “My purpose is to tell the story, to pass it on so that others may hear, see, feel and enjoy.” His contribution to the graphic novel Trickster, led to a 2010 Maverick Award, a 2011 Aesop Prize winner, and a 2011 Eisner Award nominee.

Richard Twiss (1954-2013)

Respected Lakota-Oyate Christian theologian, author, and educator, Dr. Twiss was a popular speaker and activist for Native American thought. His book, Rescuing the Gospel from the Cowboys: A Native American Expression of the Jesus Way, is considered one of the finest renderings of contemporary Native-Christian theology.

How to Respond to Injustice

Knowing that many Native American contributed to American church life, a question arises: How shall we fix the misrepresentation? Even more, how can we help mend the horrible injustice that occurred to our fellow Americans?

Though I do not have all the answers, I suggest four concrete steps.

Guidance

First, each of us needs to seek God for guidance on the condition of our own heart. True, much of the history occurred hundreds of years ago—during a time when we had little input or interaction. But how do we deal with the ramifications of the injustice today? How will we help make things right? Do European-Americans still harbor hatred?

Seek Forgiveness

Second, a public apology—an act of asking for forgiveness—is in store, both from the various religious groups that helped inflict the pain, and continually, from American leadership.

Recently, a Quaker group from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, apologized to local Native Americans. According to an article written by Thomas Gates in the Friends Journal:

“The public apology was particularly apt, as Lancaster was the site of the infamous Conestoga Massacre of 1763. A remnant of the once numerous Susquehannock Indians, who were subjugated by the Iroquois, ravaged by disease and famine, and harassed by settler militias in Maryland and Virginia, had eventually settled along the Conestoga Creek near Lancaster, on land granted to them by William Penn himself in a 1701 treaty. Their numbers had dwindled to less than two dozen, and despite the fact that they had always lived peacefully with their European neighbors, their position became precarious when hostilities along the frontier resumed in 1763…The Conestoga Massacre came to symbolize the eventual failure of William Penn’s ‘Holy Experiment.’”

Likewise, the Canadian Prime Minister, in 2008, apologized to the indigenous people of Canada for the abuses inflicted upon the First Nation’s people. In an article by DeNeen Brown, written for the Washington Post, she stated: “Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper delivered a long-anticipated apology yesterday to tens of thousands of indigenous people who as children were ripped from their families and sent to boarding schools, where many were abused as part of official government policy to ‘kill the Indian in the child.’”

And in the United states, President Obama signed the Native American Apology Resolution on December 19, 2009, taking the first steps to rectify the wrong inflicted upon the Native populations of the United States.

From these first two points listed thus far we learn that many people are taking appropriate actions. But we must continually extend a hand of forgiveness and a heart of humility to assist our fellow Native Americans.

Which leads me to my third point: We must persistently act on behalf of Native people, both politically (providing essential services afforded to all Americans) and culturally (ensuring the Native culture is not erased).

Act on Behalf of Native Americans

The physical ailments on the various reservations have not gone away and, in some cases, have increased. Widespread poverty, rising AIDS crises on some reservations (according to experts on the public broadcasting program Native American Calling), the disregard for Native wishes, and basic necessities such as running water, health care and internet access is missing for thousands of Americans. I have seen this first hand, touring various reservations and speaking with my Native American friends. These are not fabrications—they are everyday realities. In addition, we must encourage the propagation of the tribe’s culture, language, and rights. Nothing less will do.

Educate

Finally, we must educate one another. We must actively promote history as it really happened, both good and bad. And, prayerfully, hope the negative aspects will not repeat themselves. Let’s work for a peaceable kingdom, whereby God is glorified and people respected as imago dei–individuals made in the image of God.

These points are food for thought. But one thing rings clear: Native Americans have shaped not only popular music, but church and culture on a grand scale. It’s time to celebrate and teach it! Let the impact rumble in our schools and churches, thanking God for an amazing and diverse group of people.

To further understand the complex relationship between Native American people and Christianity, I recommend Martin and Nicholas book, Native Americans, Christianity, and the Reshaping of the American Religious Landscape.