To some extent, the year 2014 anticipated our contemporary culture. It was in March 2014 that Vladimir Putin formally annexed Crimea, with sights set on Ukraine. And the 2014 Ebola epidemic set the stage for the more universal and deadly COVID virus. There are other parallels between 2014 and today, but I won’t bore you with the comparisons.

Tucked in the middle of 2014, however, was a release by musician David Sylvian and poet Franz Wright entitled There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight. Nine years later, the composition continues to intrigue me.

Tucked in the middle of 2014, however, was a release by musician David Sylvian and poet Franz Wright entitled There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight. Nine years later, the composition continues to intrigue me.

All Music describes the piece as “A single 64-minute work, Sylvian’s composition features the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet reading from his collection of prose poems Kindertotenwald. (It literally translates as ‘Children Dead Forest,’ yet given Wright‘s well-documented volunteer work with children stricken by grief, ‘Children of the Dead Forest’ might be more appropriate.)…In places it recalls something approaching chamber music, but the editing and remixing put it in a thoroughly electro-acoustic context beyond that boundary.”

To listen to the 64-minute piece, one must have time and patience. But the effort is worth it. One hears a celebrated American poet of common vernacular and deep, human insight paired with a renown British musician whose career began in pop music. Two seemingly unrelated men create a marvelous work, building a beautiful edifice of sonic architecture.

I bought the CD in 2014, impressed by its scope and commitment to experimental music, a combination of modern chamber music and electroacoustic improvisation (EAI). And over the years, I have become more intrigued by the composition and the two men associated with the work, Wright passing away one year after the release of the project.

Concerning the relationship between Sylvian and Wright, All Music continues,

“If there is a ground here, it is Wright‘s voice: a weathered, weary, wheeze from his lungs (he has been struggling with cancer for years), yet wry, unsentimental, and unforgiving in his refusal to take life, circumstance, or himself too seriously, even when reflecting on his own mortality, grief, loss, or human failings. There is humor even in the blackest of situations (‘….I guess I’d describe myself as a fairly good egg in hot water…’). That said, this is a demanding listen, not so much for its length, but for Sylvian’s restless and yet deeply intimate, labyrinthine compositional architecture.”

Tiny Mixed Tapes describes the relationship with more candor,

“David Sylvian is an outlier. Comfortable in both the most minimal, stark avant-garde crevices and the grandiosity of dark pop…Here, on his newest release, he allows himself to fade completely into the background, to become an environment…his presence on the album is almost curatorial, though his careful piano gives the piece most of its mood.

“There is no songness here. Instead, Sylvian summons a lurching hybrid: part poetry reading, part 20th-century New York School composition, part ghoulish ambient improvisation…

“…But that comparison is soon thwarted by the appearance of Franz Wright, whose voice breaks what feels like an eternal pseudo-silence every 10 minutes or so over the course of the piece’s hour, before again disappearing into Sylvian’s atmospherics. To appreciate the album, a knowledge of Wright’s work (or his variety of late 20th-century poetry) could be helpful…

“Wright is a beautiful, creepy reader, and the durations between his poems serve almost as built-in zone-out atmospheres, allowing one to briefly reflect on the contents of each poem. Wright’s work is of that persuasion that seamlessly merges the uncanny, the surreal, the unpleasant with the common language of quotidian experience.”

Hefty and insightful thoughts. My interest, however, in the piece is more than just the composition; I’m intrigued by the spiritual nature of the work, both men adhering to religious worldviews integrating light metaphors.

Franz Wright became a Christian after a long battle with addiction and mental illness. As the son of Pulitzer-winning poet, James Wright, Franz Wright grew up with problems, in what he says in an Image Journal interview, were “partly due to my upbringing and my father’s absence… My mother married a man [stepfather] who was very brutal and who abused us physically.”

Wright’s problems led to seeking “drugs, sexual promiscuity, all kinds of deplorable behavior.” His addiction and mental illness became so bad he lost his teeth, seldom left his home, was unkempt, and became suicidal. But reconnecting with a former student, Beth (his future wife), and becoming a Christian changed things. When asked by Image Journal why he became a Christian, Wright replies, “I had always loved Christianity…,” and “without forgiveness, everything is dead.” But it was fellow Christians, including his wife, that sealed the deal for him. Wright states, “I believe God works through other human beings…We are the agents of this energy—love—that comes to one another, but sometimes in such a shockingly clear and overwhelming way that it can completely change your life.” After his conversion, Wright won the Pulitzer-Prize for his book, Walking to Martha’s Vineyard.

On the other hand, David Sylvian’s spiritual path has been as diverse as the music he composes. Born to a British household in 1958, Sylvian’s earliest interest in Christian themes took center stage on his solo breakthrough hit song, 1983’s Forbidden Colors. In Forbidden Colors Sylvian is questioning his faith. By the time of his early album trilogy—Brilliant Trees (1984), Gone to Earth (1986), and Secrets of the Beehive (1987), Sylvian went from a mystical-influenced form of Christianity to the Buddhist-inspired thought that directed much of his musical output in the 1990’s. Along the way, depression and life’s difficulties plagued Sylvian. If one thing is certain about Sylvian, however, it’s this: the spiritual nature of existence is of paramount importance in his work. To learn about Sylvian’s spiritual journey and his music, read Christopher E. Young’s book, On the Periphery: David Sylvian – A Biography; The Solo Years. Interestingly, Sylvian’s last solo album, Died in the Wool, returned with Christian imagery in tow.

With this background information in store, a deeper understanding of There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight becomes evident. Not only is the work highlighting two amazing artists creating marvelous work, but championing a spiritual worldview, the need for redemption, with an emphasis on light.

In There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight a human being may be the “house;” the “light” understood as spiritual transformation, or at least illumination. And this spiritual renovation happens despite the company of other houses (humans). In other words, light has its way regardless of the presence of the populace “in sight.” This light (Christ for Wright, or enlightenment for Sylvian) is primary.

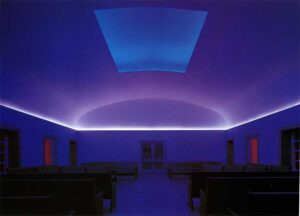

Light is a metaphor for Jesus, used throughout scripture and extended, by Jesus, to Himself: “Jesus spoke to them, saying, “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life” (John 8: 12). I’m reminded of Light and Space artist, James Turrell’s, Quaker grandmother saying to Turrell, “Pursue the Light.”

art21.org.

In Buddhist philosophy (the most recent influence upon Sylvian), light is a metaphor for enlightenment, an awakening or understanding of truth and self. In a way, Sylvian and Wright pursue the light.

With an emphasis on the contrast between darkness and illumination, There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight is more than an experimental composition; it’s a celebration of light, albeit from ill-lit spaces, both musically and lyrically. Though there is melancholy and discordant musicality in the work, in the end, the darkness of the composition makes the light brighter (found in Wright’s humor, Sylvian’s musical soundscape, or the light bathed forest found on the album cover). Or put another way, the darkness of the piece points to splashes of light, metaphorically signaling the need for sight and illumination. It’s as one scientific article observes, “everything depends on the light in some way.”

Wright’s words allude to the need for light the best. In the opening sequence of There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight, Wright talks about a blizzard in Minneapolis in 1959, feeling disturbed by its presence. Wright states, “I knew now I would have to turn on its lamp and get out of bed and try to write…” In the midst of the darkness and terror of a natural threat, Wright pursued the light.

The light-lamp is the medium upon which Wright was to create, to write. Wright needed the light. I suspect the same is true of Sylvian.

Coincidentally, in addition to the release of There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight, 2014 ushered in another discovery: the oldest human cave art, found on the Sulawesi Island in Indonesia, the caves in the Maros-Pangkep karst.

And you guessed it, scientists used light to locate the art and light (radioactive waves, similar to light) to learn more about the art. I imagine humans in the dark of the cave, outlining their hands, only to be discovered millennia later by the use of light. Light illuminated the process, both artistically and scientifically. I suppose the same can be said of Sylvian and Wright; the darkness points to the light.

It was Leonard Cohen who sang in his song Anthem, “There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.”

The cracks in both Wright’s and Sylvian’s life and work are evident in There’s A Light That Enters Houses With No Other House In Sight, with personal trials and discordant music at the forefront, but that’s how they let the light in, illuminating a way for others to see.