Frederick Hammersley and the Wonder Cabinet

Frederick Hammersley and the Wonder Cabinet

ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO —To say the three-day symposium Wonder Cabinet was a success would be an understatement. It was much, much more than that. I’d say it was worthy of its name: a wonder [1].

Working in conjunction with the Frederick Hammersley Foundation and the Tamarind Institute, the event was advertised as “Precision and Imagination, a weekend-long Wonder Cabinet, pitched squarely along the borderlands between Art & Science.” Host and co-creator Lawrence Weschler is no stranger to wonder in the world. As an author of books about artists, musicians, and scientists—and a former journalist and humanities director at NYU, he’s the perfect fit for the inaugural event in New Mexico. And with over twenty guest speakers, presentations, panel discussions, and art, the event could be summarized as a festival of awe for the amount of information covered.

But because there was so much fascinating information, it would be a disservice for me to try to unpack it all. Instead, I’ll focus in on the one topic that encouraged me to attend, artist Frederick Hammersley.

Over the three-day event there were two presentations dedicated to Hammersley and his art. Tamarind Master Printer Ash Armenta led one presentation. His discussion revolved around the progress and innovations of Hammersly’s lithographic work, noting the precision of Hammersley’s hand-written notes and unique stylistic elements found within the prints. The second presentation was by author and Director of LA Louver, Elizabeth East, and author, Dr. Joseph Traugott. Both East and Traugott provided an overview of Hammersley’s life, work, and influence.

So who is Hammersley? A short word will do.

So who is Hammersley? A short word will do.

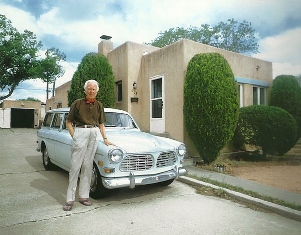

Born in Salt Lake City, Utah in 1919, Hammersley was one of the leading abstract, Hard-edge artists known as the California Classicists. After school in California and France, service in the military, and teaching, Hammersley re-located to New Mexico in 1968, first as an instructor at the University of New Mexico and then as an independent, full-time artist. He died in Albuquerque in 2009. Since his death, Hammersley has fast become one of more studied West coast artists due to his work in various fields—realism, abstract, computer, and printing, and his meticulous, almost scientific hand-written notes.

My interest in Hammersley is both personal (a favorite artist since my teenage years) and professional, as one who studies the intersection of philosophical transcedentals (unity, truth, beauty, and goodness) within education and culture. I have found Hammersley’s art a fine representation of the four transcendentals.

A quick word on the transcendentals.

The transcendentals are a sub category in philosophy that corresponds to being; they deal with ontology. Though unified, modernism has dissected them to science (truth), beauty (aesthetics), and religion (goodness). But this is a simplification; historically they were conjoined properties of being. All cultures have dealt with the transcendentals on one level or another. In the West—in ancient Greece, Plato, Pythagoras, Socrates, and Aristotle all had something to say about the transcendentals. During the first century, Paul of Tarsus interwove the transcententals in a broader fabric, best seen in his letter to the Philippians, chapter 4:8. In the Middle Ages thinkers such as Plotinus, Pseudo-Dionysius, and Augustine weighed in on the areas. But it was Thomas Aquinas, and later Immanuel Kant, who helped shape a modern understanding them as both an objective reality and a subjective experience.

When the transcendentals are used as a framework to study Hammersley’s work, the four areas act as a springboard towards a broader understanding of his art. As a concise overview, here are some thoughts.

When the transcendentals are used as a framework to study Hammersley’s work, the four areas act as a springboard towards a broader understanding of his art. As a concise overview, here are some thoughts.

Truth. According to the correspondence understanding, truth is that which corresponds to reality. And at times numbers and geometry represent the purest form of reality, coming closest to describing physical truth with the least variation (though not perfect as logician Kurt Gödel demonstrated). As noted above, Hammersley was a meticulous note-taker and artist, writing down every aspect of his process. As such, his work could be seen as scientific (something noted during the Wonder Cabinet symposium). Additionally, one could say he was the master of the line: pure, even, and precise. And when you add to his art computer generated numbers, geometrical and organic shapes, meticulous painting and use of color—truth is one of the facets that undergird his artwork. Or said another way, the truth of his lines, color, and forms correspond to reality; they are an aspect of being. Hammersley’s work is true.

Beauty. It was Augustine who said, “The eyes delight in beautiful shapes of different sorts and bright and attractive colors.” And Aquinas stated, “A thing is called beautiful when the mere apprehension of it gives us pleasure.” With these three basic understandings of beauty—shape, color and pleasure, Hammersley’s work clearly is beautiful, providing the senses pleasure with fantastic forms and color. Furthermore, Aquinas believed that beauty held certain properties. These properties were proportion, integrity, and clarity. Other interpreters have translated the words as wholeness, harmony, and splendor. And still more variation as form, radiance, and order. Whatever the translation, Hammersley’s work is consumed and radiates beauty in proportion, integrity, and clarity. As such, his work is beautiful. Interestingly, all the speakers at the Wonder Cabinet symposium noted Hammersley’s reaction to beauty: he’d often cry when he saw or experienced something beautiful.

Goodness. Maybe a little more difficult to describe within the artwork of Hammersley, but goodness is definitely present. According to Aquinas, “goodness adds to being a certain reality.” So goodness is connected to beauty, as it is to truth—a reality of its being. So if an object is true and beautiful, if follows that it has properties of goodness as well. Liberato Santro-Brienza states, “Goodness is the proper object of the will.” If goodness is an “object of the will,” Hammersley’s art can be seen as good, a representation of his will and creative thought, the object and outcome of goodness consummated in form. And concerning form, Luigi Pareyeson states, “form is perfect in the harmony and unity conferred upon it by its laws of coherence, complete in the mutual proportions between the whole and its parts.” If this is the case, Hammersley’s work is coherent, proportioned, and harmonious; therefore it is good. And if all else fails—and in opposition to the others, we can add John Chrysostom’s thought, “Thus, we say that each vessel, animal, and plant is good, not its formation or from its color, but from the service it renders.” If it is the service rendered in an object that makes it good, then Hammersley’s artwork fits the bill; it services the senses with deep pleasure. In all cases of goodness, Hammersley’s art achieves its affect.

Unity. The final transcendental infers a holistic, unified approach, a singular vision and object of the will, seeking coherence and undivided care. And when discussed within the transcendentals, unity is not a number, per-se, but an ontological reality based upon being. But I won’t unpack this. What can be inferred within the artwork of Hammersley is that there does appear to be a unified, creative approach to his art and life, seeking unity of aesthetic practice, even within the range of outcomes, stylistically speaking (abstract, realism, etc.). The various speakers at the Wonder Cabinet symposium touched on his dedication to art and beauty, whereby Hammersley sought a cohesive visual experience intermixed with his linguistic nuances (puns, naming of artwork, and notes.). Even with divergent outcomes (various styles), Hammersely’s work—with a nod to Hans Urs von Balthasar—is “symphonic,” finding a multiplicity of expressions within a unified structure of art; much like the various instruments, melodies, harmonic and rhythmic aspects in music find an expression—through the composer—in a symphony. Hammersley’s work is unified in a symphonic way.

Of course much more could be said about Hammersley’s relation to the transcendentals, but neither time nor space suffice. Instead I leave you with a thought—as generated by another Wonder Cabinet presenter, journalist and author, Robert Krulwich. Krulwich noted that good science writing (or any writing for that matter) invokes three things: noticing, painting, and sharing. With noticing, the person needs to pause and look at an object, taking note of its unique facets and being. In painting, notice will lead to discussion and describing. And with sharing, discussion will lead to feelings and deeper thought.

All of these traits find a place in Hammersley’s work. One must pause and notice the artwork, observing its detail, precision, and form. Next, one must paint with words describing what he or she saw, eliciting a conversation either verbally or written. And finally, one must allow his or her feelings to find a place in the form of aesthetic awe as presented in the art, something that goes from the head to the heart.

All of these traits find a place in Hammersley’s work. One must pause and notice the artwork, observing its detail, precision, and form. Next, one must paint with words describing what he or she saw, eliciting a conversation either verbally or written. And finally, one must allow his or her feelings to find a place in the form of aesthetic awe as presented in the art, something that goes from the head to the heart.

For more about Frederick Hammersley, click here: http://www.hammersleyfoundation.org